An Introduction to AI Verification

Introduction

Checking the accuracy of claims about the capabilities, safety properties, inputs and uses of artificial intelligence (AI) systems plays a key role in allowing actors to check that systems are being developed and deployed responsibly. Foundation model developers may want to demonstrate to users that their claims about running key risk evaluations prior to deployment can be trusted. Users may want guarantees that models were trained on particular datasets, or not trained on sensitive or protected data. International agreements may depend upon the ability of participants to check that other actors have excluded AI systems from specific domains (e.g., nuclear command and control). Yet, the means to reliably verify such claims have not kept pace with their growing potential importance in AI governance.

‘AI verification’ is a growing field of research and development focused on closing this gap. While computational verification has long been established in mathematics and computer science, AI verification is relatively new. As defined by Bucknall et al. it is “the process of checking whether an AI system ‘complies with a [specific] regulation, requirement, specification, or imposed condition’”. It aims to do this by producing methods for confirming the accuracy of specific claims about AI systems and their inputs. Such methods might include institutional mechanisms (e.g. third-party audits), software-based approaches (e.g. proof-checkers), or hardware solutions (e.g. chip-level verification features).

Verification has historically played an important role in technology assurance. For international agreements, verification has long served as a cornerstone of credible commitment: it enables states to build mutual trust that agreements are being upheld without relying solely on self-reported information. Notably, the concept featured prominently in nuclear disarmament contexts, where organisations like the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) developed technical and institutional mechanisms to confirm that states’ claims about fissile material stocks, reactor activity, or weapons testing were accurate and comprehensive.

Verification is not, however, limited to international governance contexts—it can function wherever trust depends on credible, externally validated information. Beyond the nuclear domain, verification frameworks have also appeared in domestic and commercial settings, albeit sometimes in less formalised ways. Supply chain audits, financial reporting standards, and environmental disclosure programs all rely on the ability of third parties or regulators to evaluate whether entities’ claims about safety, sustainability, or compliance reflect observable reality.

The scientific community, industry and governments currently lack comprehensive methods to check, attest to, or certify that claims made by a counterparty about a given AI systems’ properties, inputs, or deployment context are accurate. Verification methods face a dual challenge: the ‘Verifier’ needs them to be difficult to spoof, circumvent, or tamper with, but the ‘Prover’ needs to be sure that untrusted parties can’t use them to extract sensitive information. While some technologies such as confidential computing have already made substantial progress on this front, further research into and development of verification methods could improve the ability for multiple parties to ensure frontier AI systems are deployed credibly and safely, reinforcing both public trust and international stability.

This post explores the current state of AI verification. The first section provides a brief conceptual overview of the field. The second focuses on three types of methods for verifying claims about AI systems and their inputs: on-chip, off-chip, and personnel-based mechanisms. It then ends with a brief review of ‘trusted clusters’ as a framework for thinking about future verification solutions, and the possible role of supplementary monitoring in supporting verifiable claims.

Quick Conceptual Overview

This section provides a brief overview of the state of AI verification as of October 2025. It reviews existing literature then explores existing mechanisms and their limitations.

Verification involves two roles: the ‘Verifier’, who is responsible for checking compliance, and the ‘Prover’, who must demonstrate compliance. Verification has two basic goals: demonstrate that all declared activity follows the rules, and that no undeclared activity occurs that could be in violation of the rules (Scher and Thiergart (2024), Baker et al., (2025)).

In practice, many verification approaches centre on computing power—often referred to simply as ‘compute’. Compute encompasses the physical semiconductor chips that carry out calculations, process data, and run the instructions of AI systems. It offers several important advantages as a focal point for verification. It is detectable: training advanced AI models requires tens of thousands of cutting-edge chips, which are difficult to obtain or operate without attracting attention. It is also quantifiable: the number of chips, their capabilities, and their utilisation can all be measured (Sastry et al., 2024). This makes it a strong candidate site for verifying claims about AI systems on the basis of empirical evidence. That said, inspecting a model’s training data, code or outputs can also be useful to check whether a provider has complied with particular requirements.

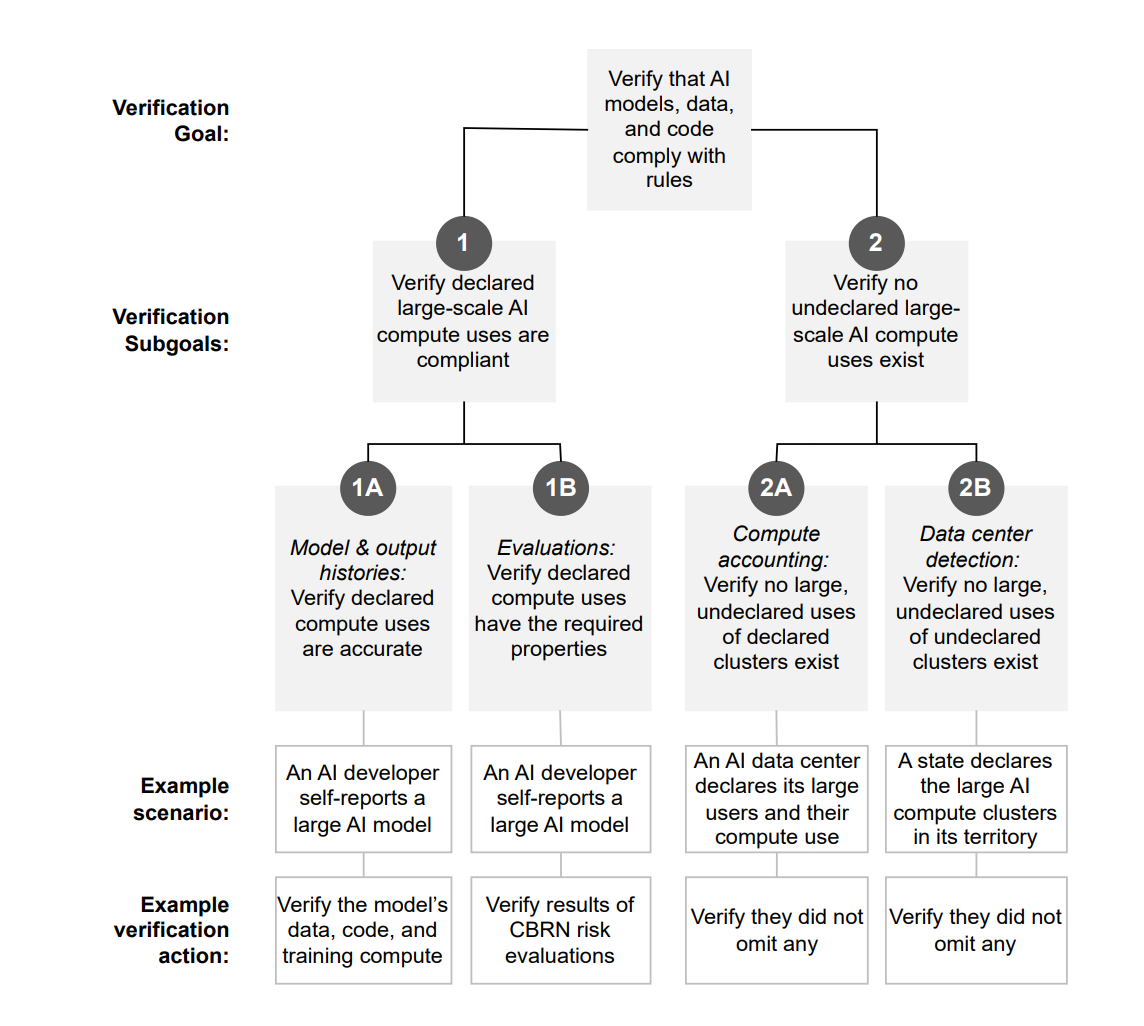

Imagine that a Verifier wants to demonstrate that all declared activity by a particular AI provider follows the rules, and that this provider hasn’t taken any other actions which might break the rules. Each of these goals can further be broken down into subgoals that can be independently checked. For example, to verify that all declared activity follows the rules, a verifier could make sure that they have an accurate transcript of how the Prover used their compute, and that this transcript demonstrates that the usage of compute was compliant. Both of these claims could be checked using different or a combination of verification methods.

A full breakdown of the different subgoals a Verifier would have to achieve to show that a provider is only training AI models in compliance with some set of rules is set out by Baker et al. (2025) in the diagram below:

How should different claims about AI systems be verified? While the particular manner of verification will depend on the type of claim, there are three main categories of mechanism: on-chip, off-chip, and personnel-based approaches (Baker et al., 2024). Each plays a complementary role and might be deployed in parallel to improve the robustness of verification. An appendix to Baker (2025) also explores supplementary intelligence measures like financial accounting and satellite surveillance, mechanisms which are also explored in more detail in Harack et al. (2025) and Wasil et al. (2024). Each of these mechanisms is discussed further in the ‘existing mechanisms’ section, below.

While recent papers come to different conclusions about the prospects for different mechanisms of verification, the broad consensus of Baker et al. (2025), Scher and Thiergart (2024) and Harack et al. (2025) is that while verifying some simple claims about frontier AI development and deployment is “likely feasible” with current low-tech measures, achieving robust confidence or verifying more precise claims would require significant R&D. As Harack et al. (2025) point out, the upshot from this is that existing mechanisms may already be sufficient to satisfy certain aspects that an international agreement could involve, like sharing particular knowledge or transferring resources like chips. For others such as preparing for emergencies, however, verification measures are still ‘in their infancy’.

In general, the field of verification is moving from a speculative research agenda to a more focused R&D stack, incorporating hardware design, confidential computing, tamper-proofing and cybersecurity, alongside further exploration of appropriate structures for institutional oversight. Both Baker et al. (2025) and Scher and Thiergart (2024) provide extensive appendices with recommendations for research priorities, whilst Harack et al. (2025) provides a strong overview of some of the key value-based trade-offs future decision-makers might face.

Existing mechanisms and their limitations

Five types of mechanisms are outlined from the literature: on-chip mechanisms, off-chip mechanisms, personnel-based strategies, trusted clusters and supplementary intelligence.

On-Chip Mechanisms

On-chip mechanisms involve hardware-level features built directly into AI chips or accelerators to prevent or detect non-compliant compute use.

Some strategies work by providing the Prover with means to make verifiable claims. One strategy, location verification, allows companies or governments to credibly prove where and how large their data centres are, thereby mitigating the risk of hidden data centres (e.g. Lucid Computing). Another strategy is to use hardware-backed workload certificates—cryptographic proofs linking a model’s outputs to particular datasets and workflows—to show how a developer trained or used a model (Baker et al., 2025).

Other strategies work by preventing the Prover from being able to act in a way that does not comply with the rules, while still allowing compliant behaviour. An example of this is offline licensing, which limits the amount of computation that can be performed before throttling or requiring renewal (Harack et al., (2025). More advanced proposals envision compliance-locked AI chips that run only approved workloads, potentially combining these mechanisms into automated, on-device compliance checks.

On-chip mechanisms promise speed, automation, and high transparency, but also face serious obstacles. Building tamper-proof hardware is complex, potentially performance-costly, and dependent on trustworthy supply chains. Moreover, if vulnerabilities were found, entire fleets of chips might need replacing. Baker et al. (2025) estimate several years of further R&D are required before on-chip verification becomes reliably non-circumventable.

Off-Chip Mechanisms

Off-chip mechanisms sit outside the chip but within the hardware stack—covering accelerators, servers, or whole data centres (Harack et al., 2025). Examples include network taps that monitor communication between AI servers within compute clusters to check for inconsistencies between declared and actual workloads (Baker et al., 2025; Harack et al., 2025), and analogue sensors that track power draw or unexpected physical activity patterns—and thereby estimate whether the total compute used matches declared workloads.

These mechanisms avoid some of the toughest hardware-security challenges of on-chip methods. They can be retrofitted, use trusted supply chains, and focus purely on observation. However, unlike on-chip mechanisms, they cannot block noncompliant actions outright. As a means to prove claims, they offer lower precision than on-chip mechanisms, and may not be as robust. Logistically, large-scale deployment could involve millions of sensors, each of which would need to be integrated with complicated hardware. In practice, then, off-chip verification is therefore likely to be more feasible than on-chip mechanisms in the near term, but would still require significant investment, and would probably provide less comprehensive and robust guarantees than mature on-chip mechanisms could.

Personnel-based Mechanisms

Personnel-based verification relies on people rather than hardware. Mechanisms might include whistleblower programs that allow employees to anonymously report non-compliance (Baker et al., 2025); structured interviews where verifiers identify violations by identifying inconsistencies in employees’ answers to interview questions. However, such interviews would have to be pre-agreed and narrowly-scoped (Baker et al., 2025; Harack et al., 2025); and physical inspections of facilities and equipment (Homewood et al., 2025).

Personnel-based measures are generally relatively simple, low-cost, and fast to deploy. They could complement technical systems by detecting or deterring collusion to bypass verification. However, their reliability is uneven. Small, trusted groups of violators could evade detection, and the relevance of personnel may decline as AI processes become more automated. In practice, personnel-based verification is a strong starting point—especially for domestic governance—but will likely need to be layered with technical measures to ensure long-term effectiveness.

Trusted Clusters

This piece has so far examined mechanisms compatible with current training and inference regimes, in which Verifiers seek to confirm claims made about a Prover’s hardware. However, this remains a substantial challenge: on-chip mechanisms are not yet fully resilient to tampering, and network sensors may be vulnerable to spoofing.

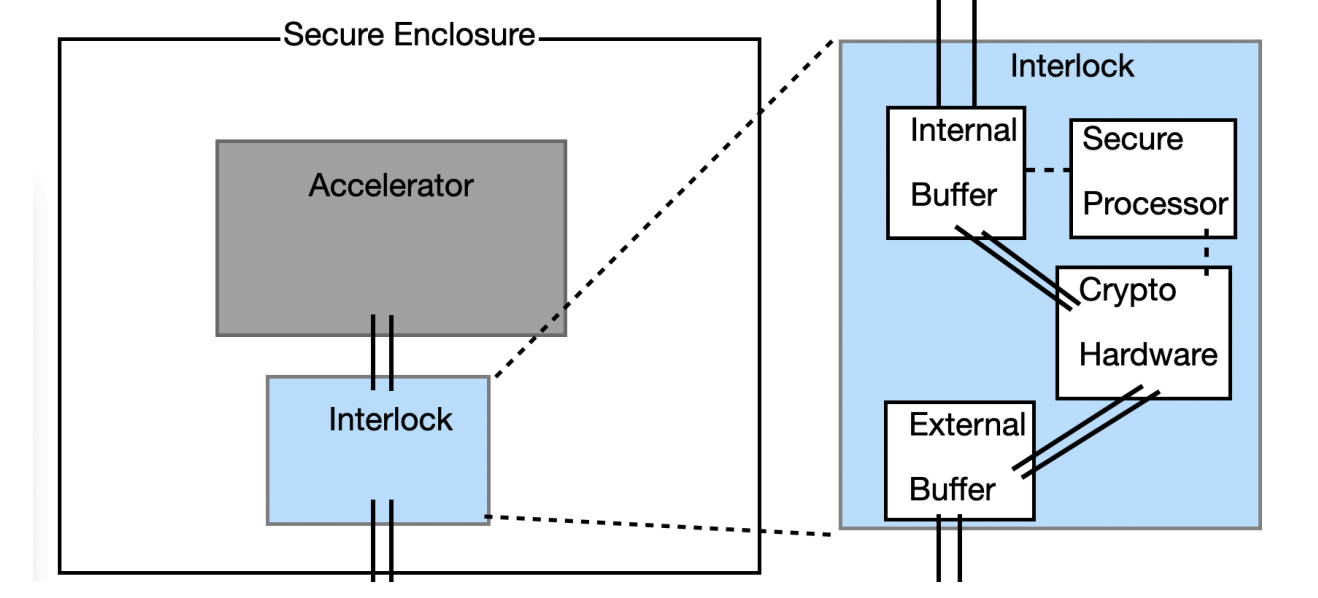

A way to avoid this might be to use the mechanisms above to build a mutually trustworthy data centre, or ‘trusted cluster’. Such a cluster could be accessed via in-person visits, like a SCIF located in a neutral territory, or be accessed via a trusted privacy-preserving API. It could be inspected by both parties of an agreement to verify that the cluster is in compliance (i.e. it won’t leak confidential information or be tampered with). In theory, this could enable a verifier to evaluate a Prover’s models, verify claims made about them, and perhaps even perform secure research (e.g. mechanistic interpretability).

The main benefit of a trusted cluster is that it eliminates the need to trust the Prover’s physical control over the hardware, network, and facility where verification happens. It’s therefore most suitable for verifying agreements that require a high level of confidence, and presume that the actor is likely to try and tamper with their hardware. Building such a cluster might be extremely costly and logistically challenging. On the other hand, it may be the best viable option in scenarios involving extremely low trust between adversarial actors.

Supplementary Monitoring

There are a wide variety of additional monitoring mechanisms that could be employed to assess whether a party is in compliance with different rules, beyond those listed above. Since many of these are already well-established practices related to intelligence gathering or open source intelligence, they aren’t explored in more detail here, but might play a role in auditing or monitoring regimes. Examples include: energy grid monitoring, financial monitoring, customs data, satellite imagery and open-source intelligence (for more see Baker et al., 2025 pp. 31-32 and Harack et al., 2025 pp 54-68).

Conclusion

This post briefly reviewed the conceptual motivations for AI verification, and five key types of mechanisms for verifying AI systems and their inputs in practice: on-chip, off-chip, and personnel based mechanisms; trusted clusters; and supplementary monitoring.

Two points are worth re-emphasising. First, that the goals of AI verification––enabling actors to make credible claims about AI systems and their inputs––may be useful in a wide variety of contexts, including for commercial and domestic regulation purposes, as well as for international agreements.

Second, that although there are now several high-profile papers on the topic, the field is still quite nascent. The broad consensus remains that while verifying some simple claims about frontier AI development and deployment is likely feasible with current low-tech measures, achieving robust confidence or verifying more precise claims would require significant R&D. Raising awareness of AI verification within AI governance and frontier AI communities worldwide—and supporting the research and industry needed to develop its underlying technologies—are the essential first steps toward enabling companies and governments to make credible claims about their systems as AI capabilities grow.

Do you have ideas relating to AI geopolitics and coordination? Send us your pitch.

Thank you for giving this important, under-appreciated area of research some exposure! There are only about one-two dozen people working on this full-time atm, most of whom I know from my own work.

Occasionally, I post my findings here on Substack, and you can DM me for more low-level details on what we are working on right now. There is a lot of work to do and time is of the essence, so if someone here thinks they can contribute, lmk!

Helpful explainer; thanks for writing!