Lessons from Source Code Inspection Facilities for AI Verification

A little-known UK-Huawei cyber security testing facility might offer a template for AI oversight

Summary

For well over a decade, a secure facility jointly operated by Huawei and British intelligence services has given the UK government unparalleled access to Huawei source code and telecom hardware for cyber security testing. The Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC) was born out of necessity; to maintain access to the UK’s lucrative telecom market, Huawei had to offer the British government strong assurances that its telecom products wouldn’t facilitate Chinese espionage and compromise UK national security.

Today, governments face a similar challenge in verifying the safety of increasingly powerful artificial intelligence systems. To address this issue, AI policy researchers have proposed trusted compute clusters: secure, government-operated facilities where AI companies could submit their models for independent verification and evaluation, without exposing their intellectual property to theft or misuse. The precedent set by HCSEC suggests that such facilities are technically feasible, and can provide credible security assurances — even in high-stakes, low-trust contexts.

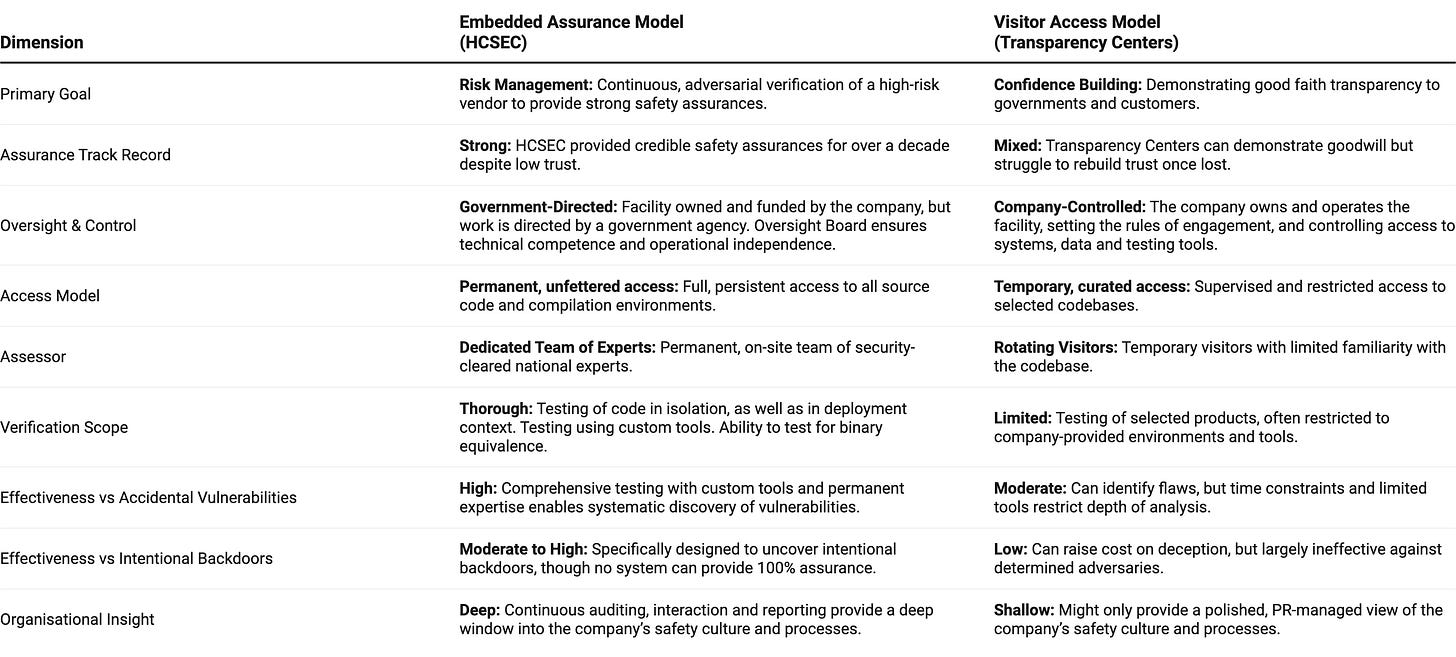

Below, we'll first take a deep dive into everything we've managed to learn about this little-known facility. We then compare HCSEC's “embedded assurance” model for source code inspections to the “visitor access” model used at Transparency Centers operated by Microsoft, Cisco, Kaspersky, Huawei, and ZTE. We conclude by discussing the main lessons from these case studies for AI verification.

While many insights are drawn from publicly available sources, we also interviewed industry experts such as John Frieslaar, who helped negotiate and set up HCSEC on behalf of Huawei, and who served as HCSEC's first managing director.

Key Takeaways

Given the right incentives, tech companies have found ways to grant governments secure access to their proprietary source code, balancing the security of their IP with the transparency needed to build trust in their products. This same transparency-security trade-off lies at the heart of many proposals for AI verification and evaluation.

HCSEC's unique “embedded assurance” model involved Huawei establishing a world-class cyber security facility on UK soil, tasked with conducting comprehensive security evaluations of all Huawei telecom software and hardware sold in the UK. While the facility was owned and funded by Huawei, its work was directed by the British intelligence agency GCHQ, and all staff were required to hold the UK's highest level of security clearance.

To protect Huawei's sensitive IP, the facility was air-gapped from the internet, with nothing coming in or out, except through two carefully controlled channels. Strict separation between HCSEC's different workstreams, as well as compartmentalisation of the facility's secure IT environment, prevented any single individual from gaining full access to the company's code.

Despite low trust in Huawei, HCSEC provided the British government with sufficient security assurances to allow the Chinese company to continue operating in the UK's critical telecom infrastructure for over a decade.

Although adapting this model for AI would present unique challenges, HCSEC provides a template for the kind of trusted compute cluster that some AI verification proposals call for.

In contrast to the “embedded assurance” model pioneered at HCSEC, over the past decade various tech companies have implemented a “visitor access” model — providing external parties with temporary access to their source code at so-called Transparency Centers.

While such Transparency Centers can help governments find accidental vulnerabilities in companies’ source code, all testing ultimately takes place in a company-controlled environment, meaning this “visitor access” model doesn’t provide enough oversight to rule out intentional backdoors.

Taken together, HCSEC and other source code inspection initiatives offer several lessons for AI verification. They demonstrate that verification in low-trust settings is possible, that it can take place even in the absence of international agreements, and that it may only require an initial investment of tens of millions of dollars to set up.

While no verification regime offers perfect assurance, even imperfect oversight would raise the bar on AI companies’ safety practices and make attempts at deception more costly. Mirroring the precedent set by HCSEC, a shared verification facility funded by participating AI developers and directed by the UK’s AI Security Institute could offer a practical path forward.

For AI governance, the question isn't whether we can design a flawless verification system, but whether we can build something good enough, soon enough, to safely navigate the risks ahead. Since hiring qualified staff and building expertise will take years, the time to start is now.

Table of Contents

The UK’s Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre

In the early 2000s Huawei was an up-and-coming name in the global telecommunications business. After years of focusing on the Chinese market, the company had built a reputation for itself in the global south, and it was now making its first tentative forays into Europe. Following smaller projects in the Netherlands and France, in 2005 the Chinese firm landed its first major contract in the UK, providing telecom infrastructure as part of British Telecom's (BT) £10 billion "21st Century Network" upgrade project. In the same year it secured a Global Framework Agreement with Vodafone — the first time a Chinese telecom equipment provider was granted Approved Supplier status within Vodafone's stringent global supply chain.

These landmark deals seemed to cement Huawei's reputation as a serious, competitively-priced alternative to Western giants such as Ericsson and Alcatel. However, around this same time concerns were starting to be raised within intelligence circles about Huawei's supposed connections to the Chinese Communist Party, and the possibility that its products could enable Chinese espionage. By 2009, just four years after the BT contract, UK lawmakers were mulling a complete ban on the use of Huawei telecom network products — a ban which had the potential to reverberate across other Western markets. To avert this outcome, Huawei approached the British government asking how it might allay these security concerns. In consultation with large network operators including BT and Vodafone, a workable compromise was found: the UK's Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC).

To learn more about this unique arrangement, we spoke to John Frieslaar, who helped negotiate and set up the operation on behalf of Huawei, and who served as HCSEC's first managing director, from late 2009 until the end of 2011.

Structure and Governance

HCSEC was established in November 2010 in Banbury, Oxfordshire, with the sole purpose of conducting comprehensive security evaluations of all Huawei telecom software and hardware used in the UK. While the facility was owned and funded by Huawei (at an initial cost of around £12 million per year), HCSEC's primary obligation was to the UK government, its work was directed by the British intelligence agency GCHQ, and all staff were required to hold the UK's highest level of security clearance, Developed Vetting (DV).

This special public-private partnership model was also reflected in HCSEC's leadership: although Frieslaar was appointed from within Huawei, his assistant director was ex-GCHQ. Subsequent managing directors included Andy Hopkins, who served for 40 years in GCHQ before joining HCSEC, David Pollington, formerly of Microsoft, who was appointed in a joint recruitment process between Huawei and GCHQ, and David Francis, a former Huawei employee.

Despite staff being on the payroll of Huawei, there was a real separation between HCSEC and its Chinese parent company. During the first two years of operation, Huawei personnel were only permitted inside the facility's secure premises on three occasions: for the opening ceremony, for a tour of the facility with Huawei board members, and several months into the programme, when Huawei sent an audit officer to verify that security measures had been properly implemented.

In addition, following recommendations from the UK's Intelligence and Security Committee, in 2014 a formal HCSEC Oversight Board was established to ensure HCSEC's technical competence and operational independence. Chaired by a senior GCHQ official and with a Huawei executive serving as deputy chair, the Board also included senior government representatives and executives from major UK telecom operators. The consultancy firm Ernst and Young was contracted to audit HCSEC's operational independence from Huawei, and over the seven years in which the Board submitted its public reports, no serious infractions of this independence were noted.

The Secure Facility

The HCSEC facility was built to the highest security standards, and its design was informed by a thorough analysis of how adversaries might try to attack or gain entry to the building. As an example of the stringent physical security measures in place, all outer doors were required to be bomb-proof, at a cost of £30,000 per door. The entire facility was under constant video surveillance, and it was divided into a small public access area and a larger, highly restricted zone. Upon entry, all staff and visitors were required to place personal belongings into lockers.

The heart of the facility was described to us as a "metal cage" — air-gapped from the internet, with nothing coming in or out, except through two strictly controlled channels:

A monitored VPN connection to China, located in a secure back room, was used exclusively to bring in Huawei’s source code and its compilation environment. This separate system was built at Huawei's insistence to ensure the secure transfer of their intellectual property.

A second secure connection was used to access information from third-party suppliers, and could only be used when witnessed and signed off by three separate parties. All documentation was scanned and approved before entering the facility.

To prevent any single individual from obtaining full access to Huawei's IP or understanding all potential attack surfaces, the facility was deliberately designed with physical separations between its four work-streams:

Software Evaluation – Reviewing and compiling source code to identify vulnerabilities.

Hardware Inspection – Analysing and understanding every single hardware component, including from third-party suppliers.

Penetration Testing – Ethical hacking of all products to simulate real-world exploitation scenarios.

Project Management – Overseeing the deployment of Huawei products into UK networks and prioritising evaluation targets based on risk assessments.

This compartmentalisation also extended to the software evaluation process itself. Within HCSEC's secure IT environment, the source code of the base operating system and that of the application software were strictly separated and were never allowed to be seen by the same teams, so that no one could get a full picture of access.

HCSEC moved to new, larger premises in 2018, to allow for a growing number of evaluations and to accommodate the deployment of multiple concurrent testing networks. While we have less details on this new facility, the Oversight Board Reports note that "the building has been assessed as sufficiently secure by HMG security teams and has also gained accreditation by Huawei HQ teams for its suitability to hold all Huawei source code".

Recruitment and Staffing

Given that HCSEC's mandate was both highly technical and security-sensitive, recruitment of qualified staff posed a persistent challenge. Amid a nationwide shortage of cyber security experts, HCSEC also had to contend with the fact that all staff had to be UK nationals who were both able and willing to obtain the stringent DV security clearance.

Obtaining DV clearance involves first passing all standard government pre-employment checks, then completing a DV Security Questionnaire and undergoing background checks on criminal records, personal finances, Security Service records and records from prior employers — before finally having an in-depth interview with a Vetting Clearance Officer. To give an idea of how intrusive this process can be, some of the topics covered in the interview include family, friends, and associations; (mental) health; alcohol and substance use; sexual history; and internet usageBackground checks and further enquiries can also extend to family members and acquaintances.

Whereas a typical company might hire one in every twelve applicants, at HCSEC this number was closer to one in 40. The Oversight Board Reports recount how in 2015, out of 359 applications, only nine individuals eventually accepted offers — and some 67 candidates failed to meet DV clearance requirements. At some point, due to a wider vetting system backlog, new recruits had to undergo a probationary period until their DV clearance had been granted (typically within six months), during which they could not enter the secure facility unless escorted by DV-cleared staff, and could not contribute directly to security evaluation reports. Within a couple of weeks of joining, all HCSEC staff received a security briefing from GCHQ and were required to sign the Official Secrets Act.

Despite these strict security requirements and associated recruitment challenges, headcount at HCSEC grew from 21 in 2013 to 39 by 2019, and the team were considered "world-class cyber security researchers and practitioners." A good training programme, generous salary scheme and career progression framework helped with staff retention. HCSEC's relatively rural Banbury location also meant that, unlike in London, the facility's engineers could not be poached away so easily by tech companies.

Assessing Huawei Source Code

To provide a bit of technical background, in software engineering, source code is human-readable text written in a programming language such as Python or C++, which defines what a program does — its instructions, logic and structure. This source code is later compiled into binaries — essentially the executable files consisting of 1s and 0s that a computer can actually run. As part of its agreement with the UK government, Huawei was contractually obliged to provide HCSEC with all components of this pipeline: the original source code, the compilation environment (the setup that translates source code into binaries), and the final shipped binaries.

Assessing Huawei code for vulnerabilities involved scrutinising the uncompiled source code, running it through checkers and highlighting errors. This code was then compiled and the resulting binaries were compared to the binaries installed in Huawei products to verify that both were in fact based on the same source code. Unfortunately, even small variations in the compilation process can result in binaries which aren't entirely identical, and obtaining full "binary equivalence" between tested binaries and shipped binaries proved to be a persistent problem at HCSEC. Even so, Frieslaar argued that the team could still verify that there were no major discrepancies between the internally compiled binaries and the China-compiled binaries. In addition, by installing both binaries on identical Huawei hardware, and conducting identical penetration testing on both setups, they could assess whether both systems responded in the same way to simulated attacks.

Evaluations at HCSEC were formalised into two categories: "product evaluations" which tested a product in isolation, and "solution evaluations" which tested products in the context of their intended deployment within the actual networks of telecom operators. The pace of testing ramped up significantly as HCSEC's tools and methods improved, with the number of product evaluations increasing from just five in 2014 to 42 in 2019. From around 2017 onward the stated objective was to test every Huawei telecom product deployed in the UK at least once every two years, and this target was broadly met.

Over time, as the efficiency of HCSEC's testing increased, so did the number of vulnerabilities encountered — though these were always attributed to poor engineering practices and bad cyber security hygiene, rather than malicious intent. Overall, hundreds of reports were sent to Huawei R&D detailing issues which needed to be resolved.

From "Productive Partnership" to "Limited Assurance"

Initially, HCSEC was seen as a productive partnership which provided benefits to all parties involved. The UK government was happy to get assurances about Huawei equipment, while UK telecom operators had full access to assess the company's source code and were essentially given a shared cyber security team to analyse Huawei gear and inform their risk management strategies. Huawei for its part was allowed to continue operating in the UK market, and could draw on insights from HCSEC to improve its products and engineering practices. Within the first two years of operation, HCSEC enabled around £300 million in new equipment sales for Huawei, and the company invested around £100 million to centralise its cyber security and code compilation processes, guided by recommendations from HCSEC. Initially Huawei also approached other governments within the Five Eyes intelligence alliance to explain the unique assurance model pioneered at HCSEC, in the hope that it could serve as a template for other countries.

The first couple of Oversight Board Reports in 2015 and 2016 continued to reflect this cautiously optimistic tone, concluding that HCSEC's work contributed to a "general increase in the standard of Huawei's cyber security" and that "the Oversight Board is confident that HCSEC is providing technical assurance of sufficient scope and quality as to be appropriate for the current stage in the assurance framework around Huawei in the UK". At the same time, these early Reports already stressed that Huawei's software did not meet industry good practice standards, and that obtaining binary equivalence was complicated by Huawei's complex build process.

In the following years, as binary equivalence continued to be elusive and new vulnerabilities were found, the tone gradually shifted — with the Oversight Board concluding that HCSEC could provide "less than ideal assurance" in 2017 and only "limited assurance" from 2018 onwards. Crucially, in 2017 the Report found that HCSEC had been receiving incomplete code packages from Huawei due to inconsistent processes within Huawei HQ. While the full source code was promptly delivered, no progress was noted on achieving binary equivalence, and "serious and systematic defects" continued to be identified in Huawei's code. By late 2018 this finally led to Huawei announcing a $2 billion plan for a company-wide transformation of its engineering practices. Even so, subsequent assessments remained sceptical, with the 2019 Report stating that "the Oversight Board has not yet seen anything to give it confidence" in Huawei's transformation plan. This confidence presumably dropped further when HCSEC found a "vulnerability of national significance" in 2019, requiring extraordinary action from UK operators to mitigate. In a particularly telling passage, the 2020 Report notes that while attempting to address this vulnerability, Huawei introduced a new major issue into the product, "showing a complete lack of security awareness".

The tone of the final Oversight Board Report published in mid-2021 (covering the period 2020) again seems somewhat more optimistic. Despite persistent quality issues, all HCSEC-discovered vulnerabilities of the prior year had been remediated, substantial progress was made on replacing an outdated third-party operating system in existing equipment, and as of 2019 Huawei was finally able to demonstrate binary equivalence across eight of its product builds. The company also committed to delivering binary equivalence for all carrier products sold in the UK from December 2020 onwards. However, by this point broader (geo)political developments had started to catch up with HCSEC. The Report notes that Huawei UK had been placed on the US Entity List in 2019, and that trade sanctions against the company had been further tightened and expanded in 2020. In practice these sanctions restricted Huawei's access to almost all US software and hardware, meaning they had “impeded or delayed the procurement or transfer of security evaluation tools and equipment”, directly impacting HCSEC's ability to carry out its work. In November 2020 the decision was therefore made to transfer HCSEC from Huawei to a new entity called Cyber Security Evaluations Limited (CSEL), as CSEL was not on the US Entity List.

The UK's Evolving Huawei Risk Mitigation Strategy

From the very beginning of Huawei's presence in the UK in 2003, GCHQ and other government institutions have treated the company as a "high-risk vendor", on the dual assumption that the Chinese state "could compel anyone in China to do anything" and "would carry out cyber attacks against the UK at some point". This meant that when BT contracted Huawei to supply telecom equipment for its 21st Century Network project, it was required to take certain risk mitigation measures. These included architecting its network to be resilient to the exploitation of any device, working with multiple equipment suppliers across its network, keeping Huawei gear out of sensitive functions such as the network "core", and having enhanced monitoring in place. At the time GCHQ also had a joint team with BT specifically to research Huawei's equipment.

HCSEC was launched in part because, from about 2008, other UK telecom operators also wanted to use Huawei products in their own networks. Rather than asking each operator to carry out parallel security assessments, from 2010 onwards all operators could draw on the work of the Huawei-funded team at HCSEC to inform their risk management strategies. The Oversight Board was added in 2014 to provide an additional layer of accountability and ensure HCSEC's operational independence. As Ian Levy, Technical Director of the National Cyber Security Centre (part of GCHQ), later explained, all of these measures were about "managing risk", and for many years that model worked pretty well. Thanks to HCSEC, the UK "knew more about Huawei, and the risks it poses, than any other country in the world", and while the facility's team of cyber security experts uncovered many flaws in Huawei's engineering, none of the vulnerabilities were ever believed to be the result of Chinese state interference.

In the end geopolitical considerations — rather than technical concerns — forced the UK to reconsider its Huawei strategy. Amid an escalating trade war with China, in 2018-2019 the Trump administration was putting pressure on allies to ban Huawei from their 5G networks. Despite Five Eyes partners such as the US, Australia, and New Zealand effectively banning Huawei in 2018, the British government stood by its assessment that the risks were manageable. This ultimately led to considerable tensions within the intelligence alliance. When senior US officials presented UK ministers with a dossier claiming to show that Huawei posed a national security risk, UK officials suggested that the document contained "no smoking gun", that some of its findings were in fact derived from HCSEC, and that having worked with Huawei for over a decade, UK intelligence had a better understanding of the risks than their counterparts across the Atlantic.

It's worth pointing out that — in addition to HCSEC's safety assurances — the government had other reasons to resist US pressure. Huawei's equipment was already deeply embedded in UK telecom networks, banning the company could dramatically delay the country's 5G roll-out, and amid ongoing Brexit negotiations, British officials were eager to maintain friendly economic ties with China. In January 2020 the British government eventually announced that, as a high-risk vendor, Huawei would only be allowed a "limited role" in the 5G network: it wouldn't be allowed in the UK's Critical National Infrastructure, in core parts of the telecom network, or at sensitive military or nuclear sites. In addition, Huawei equipment could constitute no more than 35% of each operator's network. In effect then, this was simply a continuation of the UK's existing Huawei risk mitigation strategy.

Ultimately, in May 2020 the US forced the UK's hand by tightening sanctions on Huawei, in effect cutting off the company’s access to any semiconductors designed or manufactured using US technology — including those of Huawei’s primary chip manufacturer, TSMC. With Huawei having to rebuild its entire global supply chain, GCHQ concluded that "[the new restrictions] will force significant changes to the products that Huawei supply into the UK, which will make oversight of the products significantly more challenging, and potentially impossible". In July 2020 the government announced that there would be a ban on the purchase of new Huawei 5G equipment after December 2020, and that operators would be required to remove Huawei from their 5G networks entirely by the end of 2027. HCSEC was transferred from Huawei to CSEL in November 2020 and the HCSEC Oversight Board published its last public report in 2021 — after which the Board was quietly disbanded and replaced by internal oversight within the UK's Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. However, to this day CSEL continues the work of HCSEC, providing safety assurances for all legacy Huawei equipment still present in the UK's telecom networks.

Transparency Centers

To put HCSEC's "embedded assurance" model into perspective, it's worth briefly examining the industry's prevailing "visitor access" model for external source code inspections. This approach is embodied by the Transparency Centers that various tech companies have launched over the past decade.

Origins: A Reaction to Crisis

In the 2010s, a range of incidents resulted in significant declines in trust in certain US, Russian and Chinese tech companies, prompting these companies to establish Transparency Centers in an attempt to restore confidence in their products.

A first wave of initiatives was driven by the 2013 Snowden leaks, which — among many other revelations — included evidence of Microsoft's active participation in the NSA's PRISM programme, as well as pictures of NSA agents intercepting and implanting “beacons” in Cisco servers and routers before delivery to customers. Microsoft launched its network of Transparency Centers between 2014 and 2017 and Cisco followed suit with its Transparency Service Centers in 2016.

A second wave of initiatives was driven by US sanctions and security allegations. Kaspersky launched a global network of Transparency Centers between 2018 and 2024, after the US government banned its antivirus software over alleged ties to Russian intelligence. Similarly, as the US campaigned to exclude Chinese vendors from global 5G networks, both Huawei (2018) and ZTE (2019) opened their respective Transparency Centers and Cybersecurity Labs across Europe and Asia, to counter accusations that their equipment posed a national security threat.

The "Visitor Access" Model in Practice

Though details vary, the operating model of these centres is broadly consistent. Vetted visitors — typically from government agencies or large corporate clients — are granted temporary access to a highly controlled, secure environment. Inside, they can review the source code of specific products, examine technical documentation, and in some cases perform security tests like black-box and penetration testing. Access is supervised, and visitors generally work on a private network with company-provided tools; they can also request assistance from company engineers. While some companies, like Microsoft and Cisco, allow participants to bring in their own pre-approved tools, all electronic devices are normally forbidden, and no data is permitted to leave the premises.

Within this common framework, each company's programme has distinct features:

Microsoft: The Transparency Centers are an extension of the company's long-running Government Security Program (GSP), established in 2003. This broader programme also provides approved agencies with remote, "read-only" source code access through its Code Center Premium web portal. Notable early participants in the GSP included Russia, China and NATO.

Cisco: Clients must first obtain a US export licence for the product they wish to test, a procedure which typically takes around three months. In addition, access requires payment of a service fee, and visitors are contractually obliged to report any discovered vulnerabilities back to Cisco.

Kaspersky: The company offers three tiers of access. "Blue piste" serves as a general introduction to Kaspersky's products, and its security and data management practices. "Red piste" visitors can conduct targeted source code reviews. "Black piste" visitors receive the most comprehensive level of access. Kaspersky highlights that evaluators are allowed to compile the company's software from its source code to test for binary equivalence. However, the company explicitly excludes organisations engaged in cyber-offensive operations — such as intelligence agencies — from participating in its transparency initiative.

Huawei: Access at Huawei's international centers is provided via a secure remote connection to the main code repository in Shenzhen, China. For deeper inspections, the company also allows for physical hardware analysis, which must be conducted at the Shenzhen facility.

ZTE: The company's lab in Rome has a partnership with Italy's National Interuniversity Consortium for Telecommunications (CNIT) to provide independent academic oversight of its testing activities.

Transparency or Transparency Theatre?

A crucial caveat is that nearly all public information about these centres comes from the companies themselves — via press releases, glossy websites and curated FAQs. Browsing through this material, it's difficult not to get the impression that many centers are, at least in part, sophisticated public relations exercises. Their inaugurations are often high-profile events, attended by politicians and industry leaders whose presence lends an air of legitimacy. Most company statements are thick with marketing language, and light on verifiable technical details. Of course, it is possible that many of these technical details cannot be made widely available, but are in fact accessible to governments and national security agencies.

Nevertheless, the lack of independent information makes it difficult to assess the true level of access provided, or to meaningfully compare the depth of the different programmes. On paper, some initiatives appear more rigorous than others. The ability to bring in one's own analysis tools, as offered by Microsoft and Cisco, or to test for binary equivalence, as offered by Kaspersky, suggests a more serious commitment to transparency than a simple, supervised look at the code. Even so, there are fundamental limitations to the level of assurance these sorts of Transparency Centers can provide.

The core issue is that all inspections ultimately take place in an environment completely controlled by the company. So long as the host controls the network, the hardware, the software tools, and which parts or versions of the codebase are accessible, they can fundamentally curate the reviewer's experience. Critics have argued this makes the centers "more opaque than transparent" and the visits "a bit like getting a tour of hen house security conducted by foxes".

Secondly, even with full cooperation and transparency, the sheer scale and complexity of modern software make a comprehensive audit practically infeasible within the time constraints of a temporary visit. As one expert noted, a single Cisco router might contain 30 million lines of code, so at these facilities "proving a product hasn't been tampered with by spy agencies is like trying to prove the non-existence of god".

The bottom line is that while Transparency Centers can help external parties spot accidental vulnerabilities in a company’s code, they don’t provide enough access to find purposefully hidden backdoors. As such — in contrast to the "embedded assurance" model of HCSEC — the "visitor access" model of the Transparency Centers may be of little help when dealing with a provider you don't already trust. As Ian Levy, former Technical Director of the UK's National Cyber Security Centre (part of GCHQ) remarked: "Remember HCSEC is not a ‘transparency centre’; it does much more than that and, in general, transparency centres don’t really help with High-Risk Vendor mitigation. For example, if you don’t trust the vendor, why would you believe the code they show you in the transparency centre is the code you’re running??"

In this regard it’s worth pointing out that there’s little evidence of Transparency Centers actually succeeding at rebuilding trust in a company’s products once it’s been lost. For instance, despite providing some form of source code access, these transparency initiatives have generally failed to reverse government restrictions — or to prevent them from spreading to other countries.

In China, Microsoft is still banned from government computers and servers, and Cisco is excluded from government procurement contracts. Similarly, the US ban on Kaspersky software was initially limited to government IT systems, but was later expanded to all US customers. US allies including the UK, the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, and Canada have since taken similar steps to restrict the use of Kaspersky products. In 2018 the European Parliament passed a motion labelling Kaspersky as “malicious” — advising EU states to ban the company’s software.

A similar dynamic played out with Huawei and ZTE’s 5G products. Despite these companies establishing Transparency Centers, restrictions were enacted not only in the US but also in other countries including Australia, Japan and India. Although some European nations have proven more resistant to outright bans, the European Commission designated both companies as "high-risk suppliers”, citing the potential for state interference.

Even in cases where trust-damaging incidents didn’t result in bans, it would be a stretch to claim that Transparency Centers truly succeeded at rebuilding trust. Although European customers continue to rely on Microsoft and Cisco products in the wake of the Snowden leaks, they also still use services provided by Google, Facebook, and Apple — companies that didn’t launch source code transparency initiatives following revelations of their involvement in the NSA’s PRISM programme. Rather than genuinely trusting these companies, a lack of viable alternatives and deep integration of American tech products in the European economy seem to have resulted in a reluctant acceptance of the surveillance risks.

Off-the-Record Source Code Inspections

While the Transparency Centers are all publicly disclosed programmes, many more companies have likely provided some form of source code access to governments, in order to satisfy government requirements and maintain access to lucrative markets. For instance, IBM drew significant criticism from US lawmakers in 2015 after the Wall Street Journal revealed that the company had begun complying with demands from Chinese officials to review its source code. Similarly, a 2017 Reuters investigation found that Western tech companies including Cisco, IBM, SAP, Hewlett Packard and McAfee had acceded to demands from Russian authorities to conduct source code reviews of their products. Given the security implications, it is easy to see why companies might prefer to keep such arrangements quiet, rather than risk public outcry or pushback from domestic regulators.

Lessons for AI Verification

Just as AI governance researchers have taken inspiration from nuclear arms control and financial auditing, these case studies of existing verification practices in the tech sector offer concrete lessons for AI verification.

Secure external inspections of proprietary IP are feasible

Perhaps the most important lesson is simply that — given the right incentives — companies have found ways to grant external inspectors access to their most sensitive intellectual property. This has happened repeatedly across various national security-adjacent sectors including telecommunications, cloud computing and cyber security. Microsoft's GSP, established as early as 2003, counted Russia and China among its early participants. Huawei put so much faith in HCSEC's security that the company was willing to share its source code with a Five Eyes intelligence agency — despite much of that same code presumably being used in telecom infrastructure worldwide, including in China. These arrangements demonstrate that even in low-trust, high-stakes contexts, technical and procedural safeguards can be created to balance a company's need for IP protection with a government's need for safety assurances.

The measures implemented at HCSEC — an oversight board, strict personnel vetting, air-gapped servers, compartmentalised access, controlled information flows — provide a strong precedent for the kind of trusted compute cluster that many AI verification proposals call for. While applying this model to AI would present unique challenges, the fundamental security and governance architecture has already been proven viable.

Even comparatively shallow implementations — more akin to Transparency Centers — could offer value for AI verification. While these lighter-touch approaches may not provide strong assurances against determined adversaries, the increased oversight they provide could still raise the bar for companies' safety practices, and make it much harder to hide backdoors — meaningfully raising the cost on deception. Similarly, Microsoft's remote source code access portal could provide a useful parallel for proposals to provide structured API access to frontier AI models.

Verification does not require international agreement

Crucially, none of these source code access initiatives came about as the result of an international treaty or multilateral agreement. This offers hope for AI verification. Even in worlds where AI stays in the hands of private companies — and there is insufficient state interest in reaching international agreement on AI — companies may have strong incentives to prove that their models are safe. You can still have verification from companies to governments, without government-to-government agreement.

The carrots and sticks of verification

However, the case studies also show that companies typically only embrace transparency measures when faced with the right incentives.

HCSEC demonstrates that conditional market access can be a powerful lever for governments in demanding greater transparency from foreign companies. Importantly, governments have more leverage when they have credible alternatives to turn to. The UK could make demands of Huawei partly because Ericsson, Nokia, and other telecom equipment providers offered viable alternatives. A similar dynamic might apply in AI, where the availability of domestic or allied AI capabilities affects how much pressure can be applied to foreign providers.

For domestic companies, regulation by home governments may be necessary to push companies to provide significant transparency.

Lastly, the Transparency Centers were launched following major crises of trust in tech companies, suggesting that crisis-driven adoption might follow from high-profile AI incidents that damage public trust in specific companies or the industry as a whole.

Nevertheless, for AI companies there may also be strategic value in proactive transparency. Microsoft's GSP drew minimal criticism when launched in 2003, despite including Russia and China as participants. By contrast, IBM faced significant backlash for similar source code sharing arrangements with China in 2015, when geopolitical tensions had intensified. The Transparency Center case studies demonstrate that transparency initiatives struggle to rebuild trust once distrust has taken root. For AI developers, this suggests that establishing verification mechanisms early on may prove far more effective than attempting to restore credibility after a crisis.

The hard parts get harder: operational and technical challenges will be amplified for AI

HCSEC’s operational and technical challenges highlight practical hurdles that would likely be amplified for AI verification. While HCSEC’s facility was constructed relatively quickly, recruiting qualified staff and building up the necessary expertise required significant time. The AI industry's current talent shortage and hiring competition would make recruiting qualified, security-cleared researchers even more challenging. Moreover, while HCSEC could draw on decades of established cyber security practices, AI safety evaluation is still in its infancy. Verification facilities would need to hire top researchers while simultaneously pioneering novel testing methods for dangerous emergent capabilities, alignment failures, and deceptive behaviour.

Next, keeping pace with development cycles will require a fundamentally different operational model for AI. HCSEC struggled to keep pace with an update cycle of around six months in the telecom industry — resorting to testing each Huawei product every two years. By contrast, while AI companies publish major stable releases of their flagship models every couple of months, fine-tuned and derivative models are continuously tested and deployed across different tools and use cases. As Demis Hassabis describes it, this creates a culture of “relentless building, shipping, and optimising”. What’s more, AI researchers could soon crack continual learning. As such, AI verification would need to be highly automated and capable of continuous monitoring — a shift from scheduled audits to real-time oversight, tightly integrated with developers' deployment processes.

Lastly, HCSEC struggled for years to achieve binary equivalence — proving that the source code tested in the lab actually matched the code running in telecom products deployed in the wild. For AI systems, this challenge becomes considerably more complex. Verifying model weights is just the first step, since a model's behaviour can be drastically altered by its inference-time setup. Small changes to a model’s system prompt, scaffolding, tool and API access — or even the compute budget allocated to a prompt — can fundamentally alter the model’s safety profile. While interventions such as confidential computing, proof-of-inference systems and network taps could offer partial solutions, achieving comprehensive assurance across the entire system is still an open problem.

Fortunately, HCSEC also offers a clear and viable path to funding an ambitious verification regime capable of addressing these complex challenges. At an initial cost of around £12 million per year, HCSEC was a modest investment for Huawei — particularly when set against the hundreds of millions in UK market access it enabled. Similarly, for today's leading AI companies, funding a world-class verification facility — even one costing billions annually — would represent just a fraction of what they’re spending on compute and talent acquisition. For all the technical and operational challenges, the financial burden of AI verification could be one of the easiest problems to solve.

Verification is about managing risks, not eliminating them

From the outset, the UK government’s strategy was never about proving Huawei was completely trustworthy; it was about managing the risks associated with a high-risk vendor. As such, verification shouldn’t be understood as spot checks providing definitive “safe” or “unsafe” verdicts, but rather as an ongoing process of risk management.

Importantly, HCSEC revealed deficiencies that went far beyond individual vulnerabilities. The facility provided a window into Huawei's organisational culture and processes, exposing what the Oversight Board characterised as "poor engineering practices" and "bad cyber security hygiene". HCSEC’s value lay not just in testing individual products, but in an ongoing cycle of discovery, remediation, and re-evaluation that revealed how seriously Huawei took security concerns, how effectively it responded to identified problems, and whether its internal processes were improving over time.

For AI verification, insight into a company’s safety culture may be even more critical than for traditional software. AI development involves numerous subjective judgements about model behaviour, training data, deployment conditions, and safety measures. Understanding how a company makes these decisions, how seriously it treats safety concerns, and how it balances commercial pressures against risk mitigation provides crucial context that purely technical evaluations miss.

This relationship-based approach also creates valuable feedback loops that could drive industry-wide improvements. HCSEC's ongoing oversight prompted Huawei to centralise its cyber security processes and eventually, to commit $2 billion to major engineering reforms. Similarly, even under imperfect oversight, the knowledge that external experts are continuously monitoring both technical outputs and organisational processes could create powerful incentives for AI companies to improve their safety practices.

Geopolitical tensions may trump technical assurances

Finally, HCSEC serves as a sobering reminder that even the best technical verification regimes can be undone by political tensions. Despite HCSEC providing credible safety assurances for over a decade — and finding no evidence of malicious intent in Huawei’s products — sustained pressure by the Trump administration ultimately forced the UK to ban the Chinese company from its 5G networks. US sanctions targeting Huawei’s supply chain made continued verification impossible, regardless of HCSEC’s technical findings.

For AI verification, this suggests managing expectations. While technical oversight can help build confidence, raise safety standards and create frameworks for cooperation, it cannot single-handedly overcome deep political hostility or substitute for broader diplomatic engagement. Ultimately, AI verification regimes will depend on a foundation of minimal goodwill and continued dialogue between nations.

A Path Forward

While no verification regime offers perfect assurance, HCSEC demonstrates that meaningful oversight of complex, proprietary technology is possible — today. Although adapting this model for AI would present unique challenges, the fundamental architecture has already been proven viable. Even imperfect oversight could raise the bar on safety practices and make attempts at deception more costly — as we wait for more robust hardware-enabled verification mechanisms to mature. For leading AI companies, funding a world-class facility would represent a modest investment. However, recruiting qualified staff and building expertise will take years. The time to start is now.

In the near term, HCSEC offers a template for AI companies seeking to provide credible safety assurances to governments. The UK's AI Security Institute could be a natural partner for implementation, given its technical expertise and relatively neutral position between the AI superpowers. Rather than launching individual programmes, a shared facility, funded collectively by participating AI developers, could concentrate scarce expertise and compute resources. Given there is little public documentation on HCSEC's actual facility, those looking to implement similar arrangements for AI should consider consulting with key figures involved in the initiative such as John Frieslaar, David Francis, Ciaran Martin or Ian Levy.

Looking further ahead, such an initiative could lay the groundwork for an ambitious international agreement on AI: a secure, neutral facility funded by AI developers and directed by an intergovernmental agency, tasked with verifying treaty compliance and upholding global safety standards. This could evolve from company-to-government arrangements, into bilateral and ultimately multilateral frameworks as trust and technical capacities develop.

The solution need not be perfect from the start. HCSEC shows us that oversight mechanisms evolve over time through experience, iteration and adaptation. What matters is beginning the process: learning how to balance transparency with security, building technical expertise, and creating accountability mechanisms that can adapt as both AI technology and geopolitical circumstances change. For AI governance, the question isn't whether we can design a flawless verification system, but whether we can build something good enough, soon enough, to safely navigate the risks ahead.

Future Work

While researching this piece we came across other concepts from the technology industry that may provide interesting parallels for AI governance. We’d be excited for someone to take a closer look at Project Texas — an ambitious $1.5 billion proposal to place TikTok’s US user data, algorithms and infrastructure under the supervision of Oracle. We’d be moderately excited for someone to examine the implications of source code escrow — the practice whereby a company entrusts its proprietary source code to an independent third party, which releases the code to designated beneficiaries under predetermined conditions, such as corporate insolvency.

Acknowledgements

I’m grateful to Saad Siddiqui, Mauricio Baker and Ben Norman for their insightful comments and discussions throughout the writing process. Special thanks go to John Frieslaar for generously taking the time to share his first-hand account of HCSEC’s establishment and operations.

Do you have ideas relating to AI geopolitics and coordination? Send us your pitch.